Monday, February 23, 1998

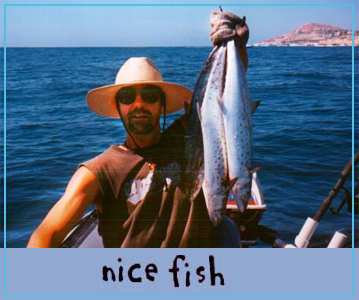

PLAYA PALMILLA, SAN JOSE DEL CABO, MEXICO -- There are those who fish and then there are those who fish. Paco belongs to the latter. You can tell by the way he doesn’t screw up his face when I tell him to be ready by 5:30 in the morning. You can tell by the way that he handles a reel; by the way that he quickly adjusts it so it is just the way he wants it. You can tell by the way he gently lowers the line into the water and lets it out as the plastic plug disappears into the blue water behind the boat, making certain in his mind that the lure is working properly. You know that Paco fishes because you can see it in his eyes as he patiently waits for the line to be torn off the reel—"It is music, no?" he tells me.

There is not much Paco actually has to tell me. His English is better than my Spanish, but generally our conversations lack much subtlety. We don’t tell each other too many fish tales. I did tell him about the time I hooked a marlin and he told me about catching sailfish in Cancun. I described Lake Superior and told him of the three hundred lakes that are within an hour of my house. He told me of the rivers he fishes in Chiapas. In the same sentence with montañas and "mi casa" I caught the word "trout. "You think you can send me some flies? There are not so many in Mexico," he asks of me. "Absolutamente."

Paco is 31. He was born in Mexico City. He has been married to Roxanna--who possesses the most enchanting smile I have ever seen--for six years. Because of the unrest in Chiapas, they have vacated their little house there and moved to San Jose del Cabo, where he is finding the business climate much to his liking. He wants to fly his dog, Flavio, over. He wants his Volkswagen Rabbit. He is making a home here in southern Baja. Last week they had a small birthday fiesta celebrating the first birthday of their daughter, Mayel (Mayan for "perfume.")

Paco makes jewelry. He sets amber, tiger-eye, black coral, and local semi-precious stones in silver. His primary place of commerce is a small piece of rented floor space in the imposing 400-room Hotel Westin-Regina. But he is not above setting up shop in the local town plaza on any pleasant Sunday afternoon. Tomorrow in Cabo San Lucas there is a big arts and crafts show where he will be showing his work. He should be at home adding to his inventory new, inexpensive jewelry to sell streetside, but he is instead out here on the Sea of Cortez fishing. For that, it is a perfect day—light chop, small swells, a cloudless Baja sky. We have been steadfastly fishing, making big loops--along the rocks, in front of the quiet, majestic homes on the beach, perhaps to tempt a grouper or snapper from its lair, then out into the ocean in search of a passing sierra mackerel or rogue dorado. We venture farther out, three or four miles, to investigate the suspicious gathering of five or six boats near the horizon. We find them to be fishing with drop-lines. We troll slowly through them and are afforded a view rarely available to one whose only access to the sea is a humble 14-foot aluminum boat. To the west we can see all the way to Cabo San Lucas, its famous arch obvious even from this distance. To the east, past Punta Gorda, is Punta Boca de Tule, half way to Cabo Pulmo. The beaches appear as only the slimmest of white lines. The entire Sierra de la Laguna range is captured in one panoramic glance, its image of impenetrability remaining uncompromised. The magic of the Baja, from out here, bobbing on the water, becomes suddenly even more tangible.

It is almost noon. We have been fishing for almost six hours. For our efforts, there are only three tiny sierra mackerel in the fish bag. As we near shore we reel up. I secure my lure, placing my pole in the pole holder. Paco switches lures. He doesn’t have to say a word.

Zelda’s diary

Whoa! There was a cow right there! Down! Wasn’t moving. I got right up close. Yuk. There were lots of smells. Cow smell. And some others. There was that smell that gives me the willies. From animals that aren’t moving. The cow was there the next day and the next. The smells kept getting weirder. There were different smells all around it. In the sand, the grass, the rocks. Lots of dog smells.

I didn’t get a lot of time to check it all out. We were always on our walk. But I did not like that cow there at all. Today it was gone. I could still smell it though. I could tell right were it had been. So I peed there.

In fact I pee everywhere there are smells. Especially where other dogs have peed. They pee. I pee. Let them know I am here. Was there. You can tell a lot by the smell of dog pee. What they eat. How old they are. What color they are. If there is a lot of pee, they are big. Female dogs have their own smells. When dogs meet they pee. Then their pee gets peed on. Sometimes they pee over the pee that was just peed. Getting’ to know each other. Just seems to be the right thing to do. Just bein’ sociable. And you know what, dogs never run out of pee. We can pee all day, whenever we want. There’s a smell, pee on it. Pee…one of life’s great little pleasures.

Oh, and we’ve been spending a lot of time on the water.

Peter's diary

After day-three its legs were now sticking straight out from its 800-pound body like a plastic toy animal tipped on its side. Traffic had created a one-lane detour around the black and white lump of cow flesh that lay festering in the middle of the dirt road, in the middle of a three-way intersection, on the edge of town, 50 meters from the Hotel Posada Señor Mañana.

The first morning of the cow, during our daily morning walk, Zelda approached the fresh carcass with raised hackles. Here lying in a heap, in the dust, was the denizen of her idle thoughts. Head lowered, ears back, an almost inaudible growl emanated from the dog as she nervously circled the fallen beast. Seldom does Zelda get this close to a cow. And it simply lay there. We continued down the road. A guest at the hotel claimed to have heard a loud "THUMP" in the night. All day the black mass remained at the bottom of the hill.

Day-two it was still there. Its stomach may have bloated, I couldn’t be sure. It was no longer a fresh kill. On our morning walk Zelda again checked out the dead animal, but this time with a little less trepidation. It still aroused her curiosity. The cow seemed to have become a simple road obstacle, like the pile of dirt that commonly appears in the middle of Mexican roads, to disappear just as mysteriously a couple days later.

Gary, the owner of the Hotel Posada Señor Mañana, made repeated calls to various San Jose del Cabo public offices to have the dead creature removed.

I began to suspect that this was one of those instances where action would have to be instituted by those to whom the situation most affected. The cow lay at the edge of town, albeit a small town. It was in a road seldom traveled by any but the most car-happy of tourists. It affected the Hotel Posada Señor Mañana. If it were left to rot, its stink would affect only a small portion of the town. If the hotel really wanted the dead cow outta there, they would undoubtedly do it themselves.

By the third day the cow’s protruded head had been run over and feral dogs had discovered the quickly rigormortising creature. It was Friday. I could only imagine the carnage that was certain to be inflicted by the weekend traffic--local rancheros speeding about on the darkened street in their single-headlighted, gerry-rigged, rattling Japanese pickups, paper bag-enclosed 36-ounce ballena beers between their legs.

Paco and I passed the bovine heap in the early daylight on the way to fish. Upon our return four hours later, only a dark stain in the sand remained where the cow once lay.