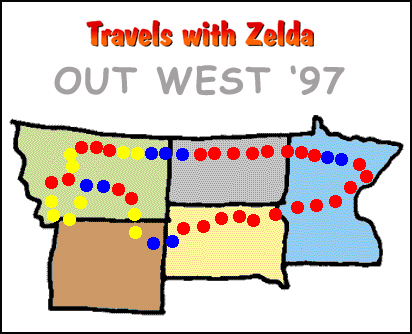

IN MONTANA

All lakes are public

Tuesday, August 12, 1997

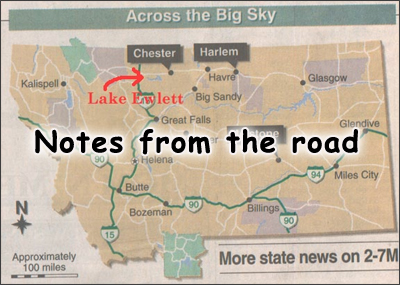

Early morning, low on gas, I drove up Rock Creek on Rock Creek Road, occasionally fishing promising stretches, reinforcing my opinion that Rock Creek requires at least four days.

The road meets the pavement after 47 miles of gravel in a sweet valley, lush with hay, birch trees, and grazing land. The road then crosses the low green hills of the Sapphire Mountains. There are spectacular overviews to the west- the immediate western side of the Sapphires and the snow-capped Bitterroots beyond. The entire climb is among giant, rounded, green forested hills. The downslope brings you into the Flint Creek Valley and the town of historical mining town of Phillipsburg.

Going north on Montana 1 to Drummond the road follows Flint Creek, a very inviting little creek that meanders in the valley, offering access here and there. Montana law proclaims all water public domain up to the high-water mark, as long as it was accessed from public land. The occasional fisherman was seen near where roads crossed the creek. This area is rich with minerals- gold, silver, phosphates, manganese, sapphires- with abandoned mining buildings scattered about.

Drummond is a dingy, depressing town, its only resource being the freeway- the on-ramps, east and west, being on opposite ends of town, generating the only traffic I can imagine. From there a steep, dirt road climbs into a very rural grassy plain, again scattered with abandoned structures.

At this point Pere Ubu’s Modern Dance is filling the van, which makes for an odd atmosphere. If I were playing George Straight, Merle, or George Jones it would be a completely different experience. With Ubu you become aware of contrast- how far this is from Akron. Right after, Non-alignment Pact, I switched to The Texas Tornadoes, not quite country, but closer in comparison.

The road hits the pavement at Helmville, an almost ghost town rife with dilapidated buildings, many seemingly inhabited. The community center was the biggest and newest building in town. Obvious, however, to this trained observer, was the real center of town, the Copper Queen Saloon, with its spacious parking lot and classic saloon styling. Still heading northeast, the Swan Range fills the view directly ahead. The road ends at Hwy 141 and we go north a few miles until the junction with Montana 200.

Highway 200 follows the Blackfoot River. Again the river is inviting as it winds up the valley. Access looks tricky, however. Behind me rise the Garnet Mountains, the northern edge of the Sapphire tectonic block that slipped east from Idaho. Here Theo Ennan and the Algorhythms knock me out, as always, as I climb to Rogers Pass, cross the Continental Divide, and ride second gear down a 6% grade onto what appears to be an ancient seabed.

It is football weather. Spending Sunday in some local bar watching football would be kinda fun, actually.

Highway 200 intersects the dreaded and haunted US 287 at Bowman’s Corner where the only landmark being a steakhouse. If I were funded better, I would think seriously about popping in for a nice civilized meal. As it is, restaurants are not in my itinerary.

US 287 lies in an area geologically known as the Disturbed Zone. I think, "How apropos." It was on the southern end of this possessed stretch of pavement where my extended bout of bad luck ensued, the loss of my fly rod being the foremost occurrence.

Traveling north one gets the real sense of being on an ocean bottom. Gentle, undulating hills, and sedimentary outcroppings dominate the landscape.

To the far east are the Abel Mountains, known to some as the Birdtail Mountains. These are mostly of volcanic origin. Distinctly nearer east is Haystack Butte, an isolated pointed peak of unknown history. It is assumed to be an igneous intrusion. It looks to me like a cute, little, eroded volcano.

Dead ahead are huge striated cliff-faces, the tops hidden by dark gray, hovering clouds. The dirt road winds among the moraines, the opening of the canyon becoming more awesome as I near. The road becomes paved (thanks to the dam and the Corps of Army Engineers) and enters the steep Sun River Canyon, the multi-colored limestone walls going straight up and straight down.

The road continues through a series of narrower canyons, all a part of the front edge of the Sawtooth Mountains. By now the sun is gone. Billie Holiday, The Verve Years is bringing me down the stretch. Gibson Dam looms between the canyon walls. The Sun River flows fast, clear, and cold along the canyon floor. The day has unexpectedly been…well, spectacular.

Fishing Report

Oh, those guys…Marj and Jay Crawford…sending me all the way up to Skalkaho Pass…to cross over the Sapphire Mountains to Rock Creek…oh, those kidders. I get all the way up to Skalkaho Falls and the pass is closed. It’s getting late, my plans for fishing Rock Creek that evening dashed.

The Bitterroot Mountains are a spectacular backdrop with their rugged, snow-capped, granite outcroppings and sudden deep gorges, especially when compared to the older, rounder Sapphire Mountains on the east side of the Bitterroot River.

If I were to never fish and explore any two Montana rivers other than the Big Hole River and Rock Creek, I would be a much-contented man. Rock Creek is everything a river should be: accessible along almost its entire length, the water is varied from rushing whitewater to meandering oxbows, the available campsites are plenty, the surrounding mountains are inviting and picturesque, and there are plenty of fish, although I didn’t catch but one ten inch rainbow. I would have liked another three days to challenge it.

Gibson Reservoir- Funny thing about canyons- the wind is either always at your back or in your face. Gibson Reservoir is seven miles long, making four or five broad snaking turns around towering mountains, roughly following the original course of the Sun River which flows into it at the north end. Here the North and South forks come together, both forks offer very inviting fishing hike-ins.

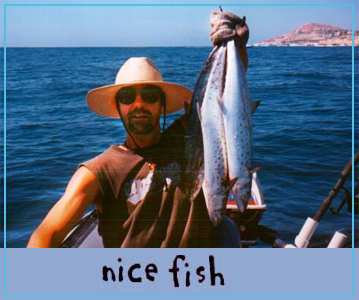

This end of the reservoir abuts up next to the Big Bob- Montana’s superb wilderness area. The day was splendid. A gentle wind blew from the southeast, pushing the canoe up the reservoir. The sun shone high in the sky. It was just after one in the afternoon. Trolling the flutter-spoon rig that worked so well at Wade Lake, rainbows were striking every 15 minutes or so. Pan-fryers. Eight to eleven inches.

It was a gas. I figure it took me less than two hours to get to the end of the reservoir. I was marginally concerned about the time, even though I got a rather late start. Where the river enters the reservoir, it makes a deep pool, churning like a giant hot tub, fifty feet long by twenty feet across.

From it I pulled three ten-inch rainbows on a grasshopper fly. From the pool, the water flows into a mini-canyon, thirty-foot walls, deep, calm, gently swirling green water. Under most circumstances, it is an unfishable stretch of river, unless one had, say, a canoe, which could be dragged upstream for a short distance and then paddled in the mild current into the canyon.

And it doesn’t see many canoes, since, firstly, Montanans aren’t canoeists and secondly, paddling the seven miles is a bit of a natural deterrent to start with. Fishing the little canyon was very cool. Just spacious enough to operate a fly rod, allowing flies to be tossed under ledges and into little pools.

Almost every cast brought action. The 45 minutes I spent being spun around by the swirling winds and currents, I caught and released a dozen and a half rainbows. With four fish in my creel and the possession limit being five, I was waiting for that 20-incher. But, alas, no granddaddy here, and it was time to head back.

While I was playing around, oblivious to much around me, the wind had continued to build. When I re-entered the lake, the wind was tearing at my hat. Whitecaps were streaming down the canyon right into my face.

Seven miles into a 20-mile an hour blast.

Ranger Barb had mentioned the water could get nasty.

As I write this, the waitress at the Wagon’s West Café, who spent nine years working at the reservoir, tells me the wind can get like a hurricane coming down the canyon. She says she has hiked the trail that runs along the north side of the reservoir, 50 or 60 feet above the water and has gotten soaked by the spray kicked up by the wind. She talks about boats, which normally make the lake-length run in ten minutes, taking 45 minutes to get from the lake head to the dam.

The waves didn’t concern me- there wasn’t enough distance to generate dangerous waves. But the wind! An alee side of the lake didn’t exist. The wind followed the canyon like a current. The wind would make 180-degree turns. No matter where I was, the wind was in my face. If the nose of the canoe strayed from directly into the wind past a critical point, there was no bringing it back.

The canoe had to be paddled to shore and physically repositioned. Much time was spent making no forward progress at all, all energy being concentrated at keeping the bow into the wind. The few boats that went by simply stared.

The shoreline crept past. After several hours, my arms ached. I’ve been in wind before, maybe not quite like this, but it is still just a matter of paddling, slowly but surely. Nose into the wind. Keep paddling. I was hoping as the sun dropped, so would the wind. It did.

About two thirds of the way across the lake the wind began to subside. I tossed out the trolling rig and ambled home, enjoying the spectacular scenery as the colors changed minute by minute.

While I never complete my limit with the 20-incher, I did bring my five fish back, catching another half dozen during the final third of the four-hour homeward journey. It was after 8:30. Just time for three pan-fried trout, hashbrowns, and two or three Lucky Lagers. I slept fine.

Gibson Dam