In Lemmon SD

Slowed to a crawl

Monday, July 28, 1997

Bearlodge Campground, Black Hills National Forest, Wyoming -- The following tale is from a copied pamphlet found amongst tourist literature at the Petrified Wood Park in Lemmon, South Dakota.

Long before there was a South Dakota, a loner named Hugh Glass, mauled by a bear and deserted by friends, crawled 200 miles to safety and into the annals of western history.

Hugh Glass: the survivor

The story of Hugh Glass and his fight with an enraged grizzly, his desertion by fellow trappers, and his agonizing crawl back to civilization ranks as one of the most incredible true-life dramas ever recorded.

Yet this episode, which began in late August of 1823 along the Grand River in what is now northwestern South Dakota, was merely one chapter in a long life of adventure lived by Hugh Glass.

Despite the renown of Hugh Glass, however, this man who was carried into the realm of folklore by a grizzly bear remains largely unknown. His origin is shrouded in mystery. An item which appeared in the Pittsburgh (Pa.)Gazette on April 23, 1795, offering a six pence reward for "Hugh Cook Glass, about 20 years of age," an apprentice gunsmith who stole a rifle and ran away from his employer, has been suggested as being a reference to the Hugh Glass of history. No conclusive evidence has yet been presented, however, which definitely identifies one man with the other.

Hugh and his unnamed companion made their way to the plains, where eventually they fell captive to a band of Wolf Pawnees. This tribe is known from historical records to have offered up human sacrifices, and this also was the fate prescribed for their two new captives. Hugh’s companion was seized as the first sacrifice, and after being stripped, bound, and his body stuck throughout with splinters of pitch-pine, he screamed out his life as the pine splinters were torched and he was engulfed in a blazing inferno.

Hugh was forced to witness the spectacle, knowing that he would share the same fate, and yet when the time came, Hugh displayed no tremor. Instead, he pulled from his pocket a small packet of vermillion and offered it to the chief with a bow of farewell. The Indian, appreciating a courage rarely seen, returned Hugh’s sign of respect by deeming such a man unworthy of sacrifice, and Hugh was allowed to live.

Not long after, Hugh accompanied a delegation of the tribe to St. Louis for a meeting with territorial officials, and there he remained until joining the Ashley-Henry expedition.

Only a few weeks after sending his letter of condolence to the family of John S, Gardner, Hugh Glass was among a small group of men led by Andrew Henry who started overland along the Grand River toward the Yellowstone.

Several days later, while traveling apart from the main party as usual, Hugh was surprised and attacked by a mother grizzly with two cubs. Hearing his screams, fellow trappers rushed to his aid and killed the grizzly which had been wounded by Hugh. Horribly mauled, his wounds were crudely dressed with the materials at hand and he was carried along in a hand litter for several days by his companions, who waited for him to die.

At length, wishing to facilitate and hasten their march to the Yellowstone, Henry asked for volunteers to stay with Glass until he died, and then to bury his body With a promise of monetary compensation, John S Fitzgerald and nineteen year old James Bridger agreed to stay.

Several days passed, and with Hugh stll clinging to life, Fitzgerald and Bridger, no doubt in fear of being found by roving bands of hostile Indians who had battled the trappers all season, packed up Hugh’s rifle, knife, and other equipment and hurried on after Henry’s men. They reported that Glass was dead and buried, showing his possessions as proof.

Hugh, of course, although racked by fever and infection, was not dead, and soon, barely able to crawl, he started back toward Fort Kiowa on the Missouri River, more than 200 miles distant.

Incredibly, convalescing as he went and living for the most part on roots and berries, Hugh Glass did reach Fort Kiowa, six weeks later, and immediately set out to find the two men who had deserted him and stolen his prized rifle.

Weeks later he found Jim Bridger at Andrew Henry’s recently established fur trading post on the Yellowstone River near the mouth of the Big Horn. He did not kill Bridger, as he must have sworn to do during his long crawl, but instead reportedly excused Bridger because of his youth, and left him to answer to his own conscience and to his own God. Hugh did not find Fitzgerald until some time later, discovering that he had enlisted in the army at Fort Atkinson, near present Omaha, Nebraska. Hugh likewise did not kill Fitzgerald, perhaps mainly because the killing of a U.S. soldier carried severe consequences. At any rate, he also left Fitzgerald to answer to a higher authority, at last recovered his stolen weapons, and resumed his career as a free trapper and hunter.

Hugh soon traveled to Taos, present-day New Mexico, and on a later expedition to the Rocky Mountains he was struck in the back by an arrow during a confrontation with hostile Indians. The shaft snapped off, and he carried the point embedded in the bone of his back for a reported distance of 700 miles back to Taos before a razor could be obtained which a comrade used to cut the arrowhead out of the swollen and inflamed wound.

Hugh Glass’ life came to an end in the early days of 1833, when he and two companions left Fort Cass, on the site of the earlier post of Andrew Henry, and started down the frozen Yellowstone on a hunting and trapping excursion. They had proceeded only a few miles from the fort when a roving band of Arikaras jumped at them from the bank, and Hugh Glass, who had become a legend in his own time, at last fell in death beside his two companions.

About the author- Mr Ellison is a young Lemmon rancher who enjoys writing of this region’s history. He previously authored articles for South Dakota Magazine on the Custer battle and the Black Hill’s first gunfight.

Rush To Nowhere (Where Are You Safe) update:

KGFX 1060 AM, the powerhouse out of Aberdeen reaches all the way to just south of Lemmon and as far west as just east of Buffalo, almost entirely across the state. Since it was after even delayed broadcast time, I was unable to ascertain whether the airwaves carried Rush south from there. I assume that somewhere in the Black Hills there is a radio station that carries the EIB Network. So, one might be safe, for the first time since I left Minneapolis, somewhere between Sturgis/Deadwood/Rapid City and Lemmon, SoDak. But I’m just guessing.

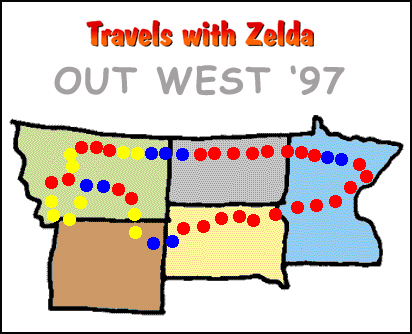

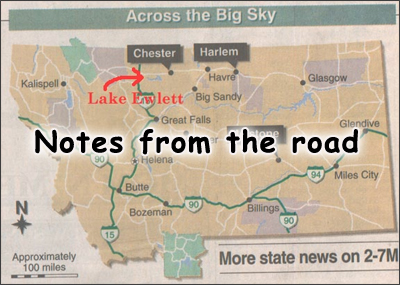

Travel notes: yesterday I put on some miles, something I have great endurance for. Of course, right off the bat I took a wrong turn just outside Mobridge. Went north to McLaughlin on hwy 12 instead of taking the "left" onto hwy 20. Cost me about an hour.

Bearlodge Campground, Black Hills National Forest, Wyoming